I’ve spent summers in Las Vegas gated communities, looking outwards.

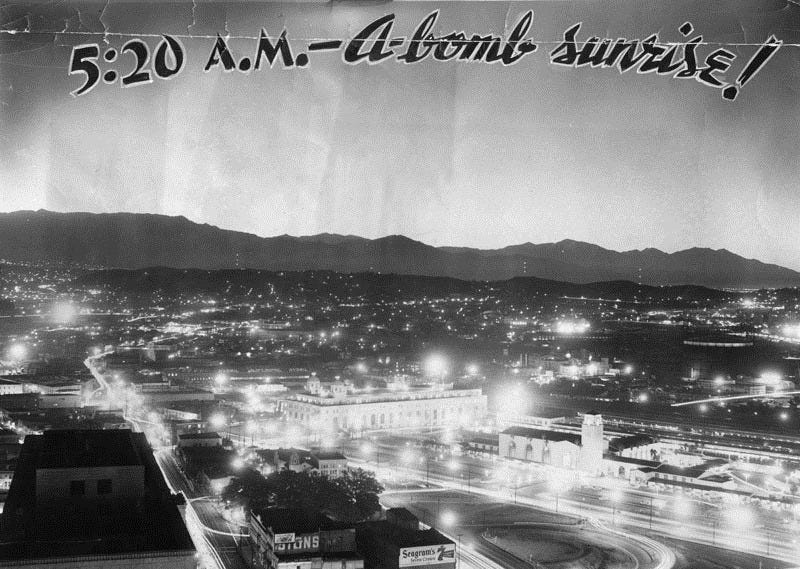

Las Vegas is a meaningful city within the American cultural imagination, especially in terms of design. The iconographic mushroom cloud is a frequent symbol along the strip’s universe of neon lights. The memorable slogan “Born in America’s Defense” is advertised throughout the local suburbs. Southeast, Henderson is steeped in this shrine to the military.

During the Cold War, the U.S. defense industry located its most prolific Nuclear Test Site less than one-hundred miles away from Las Vegas. The city ballooned quickly outwards, making room for workers involved in the production and testing of weapons. Fifty years later, the urban vernacular of Las Vegas reflects a cultural dream of explosive possibility, a symbolic commitment to class ascension and economic prosperity. Las Vegas’ universe of neon lights characterized by the celestial, upward facing nuclear cloud, creating a good image for itself. Its given way to a new local cloud industry, tech warehouses and databases, which are becoming increasingly common in the area. In 2020, Henderson became home to the largest Google cloud center in the U.S. West, supporting its AI technologies.

The architectural contours of a Google Data Center are not obviously perceived as a continuation of Las Vegas’ local architectural traditions. For instance, Learning from Las Vegas (1972), the seminal case study by architects investigating the complexity of urban symbols in Las Vegas, paints Las Vegas as a communicative landscape. Billboards provide utility for the public. Symbolic communication is intentionally designed to welcome visitors and patrons through speaking across distances in a landscape shaped by the automobile.

The Google data center in Las Vegas is a cloud data center housing both data from Western U.S. users and supporting its cloud AI. Upon first glance, the data center is a complete aberration of the architectural tradition of Las Vegas. Even positioned upon a major throughway, the Google Data Center ominously has no symbolism or decoration upon its facade, lacking in the postmodern vernacular of bright, large, graphic, and direct communication that the Las Vegas Strip has pioneered. The google data center is essentially a gargantuan warehouse, ominous, nihilistic, emotionless, the drill subgenre of architecture.

The design of the invisible is a strategic one. Returning to the defense industry, the history of camouflage is one of obfuscation. Camouflage was invented throughout WWI and WWII by renowned artists with conceptual depth. The avant-garde, such as the surrealist Roland Penrose, were recruited for its development because of their expert interplay of figure and ground boundaries informing uniquely deceptive patterns. Even further, the Cubist sensibilities of Picasso were deployed to manipulate light and shade to flatten three dimensional space into two dimensional compositions integral to the camouflage techniques of distortion and environmental mimicry. In the case of data centers, the buildings maintain this style integral to the material affair of war.

Data centers are often blank and low, and thus receding into the landscape. The low to the ground, two-story and wide cubic shape of the buildings draw them down into the landscape rather than up towards the skyline, producing an illusion of flattening and blending. The low profile casts a smaller shadow, playing on horizon line and light in a manner that flattens three dimensionality. Furthermore, the very color of data centers mimic the natural shade of the surrounding environment. These formal visual relationships between data centers and camouflage show that data centers are not an invisible object situated within a history of visual obfuscation, but rooted in a history of defense aesthetics.

An image of Picasso’s camouflage.

This is reinforced by the expansive site barriers and links of data centers, clearly the result of significant planning and effort. The data center in Henderson has two fences stretching around the entire perimeter of the 64 acre site. Technologies of defense are extensively deployed by the data center, including cameras, guards, and security alarm systems. With attention to these details, the appearance of this data center conveys a sensibility of national security, camouflaging the capabilities held within.

The reason why I’m drawing attention to the similarity between the architectural forms of tech and the defense industry is because of the misleading media coverage surrounding the development of tech. Favorable media portrayals of data centers push a utopian potential of platforms. Political figureheads and news anchors frequently tout the employment benefits of data centers, making it clear that politicians across different levels of government endorse Google’s public campaign: the data center will benefit your state on the basis of job growth. In one Henderson article, the Director of Economic Development and Tourism outlined their enthusiasm about Google: “This is a great opportunity for us to align with tech companies and create a story around how we’re diversifying our economy.” Likewise, Nevada State Senator Catherine Cortez Masto said: “I’m excited about the jobs that this investment will bring to Nevada, as well as the fact that this investment in innovation is taking place in our state...” This sentiment is again echoed in other sectors of the government, with the mayor of the City of Henderson asserting: “As Nevada’s premier community, we’re absolutely thrilled to welcome Google and its local workforce to Henderson”.

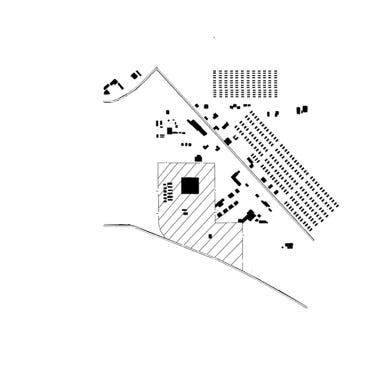

The local reporting in Henderson unfailingly naturalizes the instantiation of the data center by making it appear like the logical future of the place. However, the architecture of data centers, as I’ve discussed, are a continuation of the aesthetics of the U.S. defense industry. Google’s public articles of incorporation contradict the data center’s presumptive benefits directly. The claim that the data center will bring employment to the region is specified within the legal agreements and business application between Google and the state of Nevada, where the data center commits to hire only 50 workers in Henderson. This number seems astronomically lower than what the media discourse promises. Note also that the data center, alongside limited job growth, has already led to significant increases in rental prices in the surrounding area. Price increases of 300% are not uncommon, which has caused major disruptions in a real estate market where such a jump was unprecedented “5-10 years ago.” For a company with a market cap of 1 trillion dollars, the impact on the surrounding community looks grim, and indeed, much like the trends we’re seeing in the San Francisco Bay Area. A to-scale figure ground relationship between the data center and the community by the author, depicting the data center dwarfing the surrounding community:

A to-scale figure ground relationship between the data center and the community by the author, depicting the data center dwarfing the surrounding community.

Peering into the architectural history of Las Vegas, it is easy to question the recurring confidence in schemes for the reinvention of Las Vegas. Is a Google cloud just another nuclear bomb? A data center, sharing visual similarities with the defense industry, and similarly boasting federal funding, shares more continuity with local histories than one might initially assume. This is alarming, nonetheless, given the many cultural allusions to the mushroom cloud obfuscated from view the stark patterns of illness and joblessness in local communities that followed magnesium production and local nuclear testing. Las Vegas’ place-based transition builds upon a history of local exploitation, and the implications of this long-standing process is yet to be more fully understood.

The area has gone from providing employment opportunities for the working and middle classes to endemic precarity for these demographics. The Basic Magnesium Plant in Henderson had a labor force numbering 14,000 in the 1940s, and as previously discussed, the Google data center will only have a labor force of 50 people. This transition to a post-labor city is advancing in tandem with misleading discursive practices in the mainstream media. As discovered through an analysis of the visual dimensions of the data center, there is evidence of these corporatist values are seen in its architectural form. Policy makers have long given up public assets, such as land, sunlight, and hydroelectric power, which the Las Vegas area is replete with, for short term political exploitation and private profit. These are processes that the community have been subject to since the inception of the city. All of these conditions align with an understanding of technology as not inaugurating, but benefiting from and continuing a process of state power. The question now is whether there is a way to delink the architecture of platforms and that of an equally violent past. As Walter Gropius once famously said, “Together let us desire, conceive, and create the new structure of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will one day rise toward Heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.”